In 2015, the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) adopted 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) intended to be achieved by the year 2030. As UNDP mentions, the sustainable development goals are a universal call to action to end poverty, protect the planet and ensure that by 2030 all people enjoy peace and prosperity[1].

These are times of unprecedented challenges. In many ways the effects of COVID-19 are yet to find way into official statistics but are indirectly evidenced through multiple indicators. Income disparity, as recent studies have revealed, has widened sharply, as has gender disparity. Millions of people have been pushed into poverty and businesses especially MSMEs have been deeply impacted. Community and familial bonds have been shaken. Climate change can potentially compound these challenges. Through the COVID-19 affected period, repeated climate events of increased intensity have come to indicate that the time for procrastination is over.

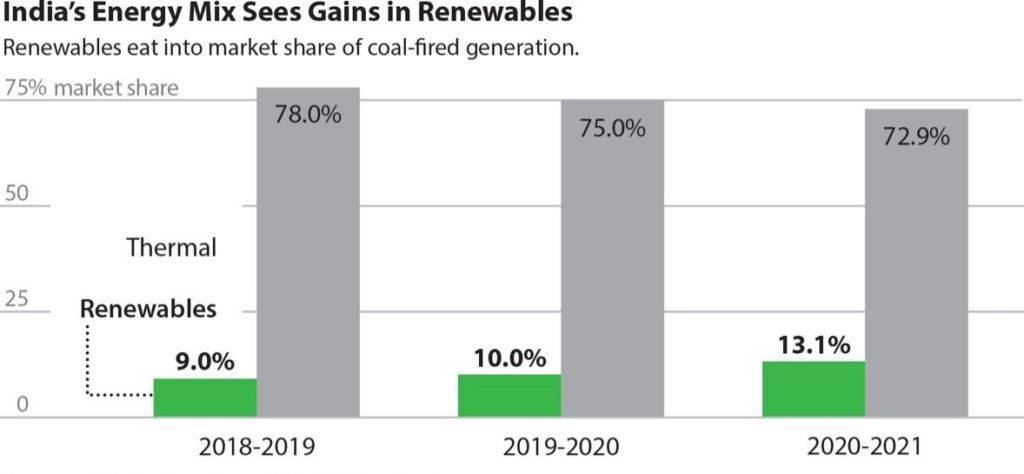

For India, with its imperatives of bringing masses out of poverty and ensuring decent standards of living for all, these have significant imperatives. Energy and the environment are umbilically linked. Initiatives to curtail emissions, while entirely necessary, have to be undertaken without impeding economic and energy supply growth. Within the energy landscape, electricity will have a key play since in future most energy delivery is forecast to be through electricity[2]. This has very specific implications for India. Over the past several decades India’s energy supply has come to be heavily reliant on coal. While nominally just over half of the installed capacity is coal fired[3], much of the actual electricity generation (~73%) is from coal (see figure below). Hydro, a previous mainstay, has slowed down. India has scripted a very creditable story on renewables, which has touched 100 GW, excluding large hydro and 146 GW when large hydro is included[4]. However, the overall contribution of renewables in the energy system, albeit growing rapidly, is just over 13% (see figure below).

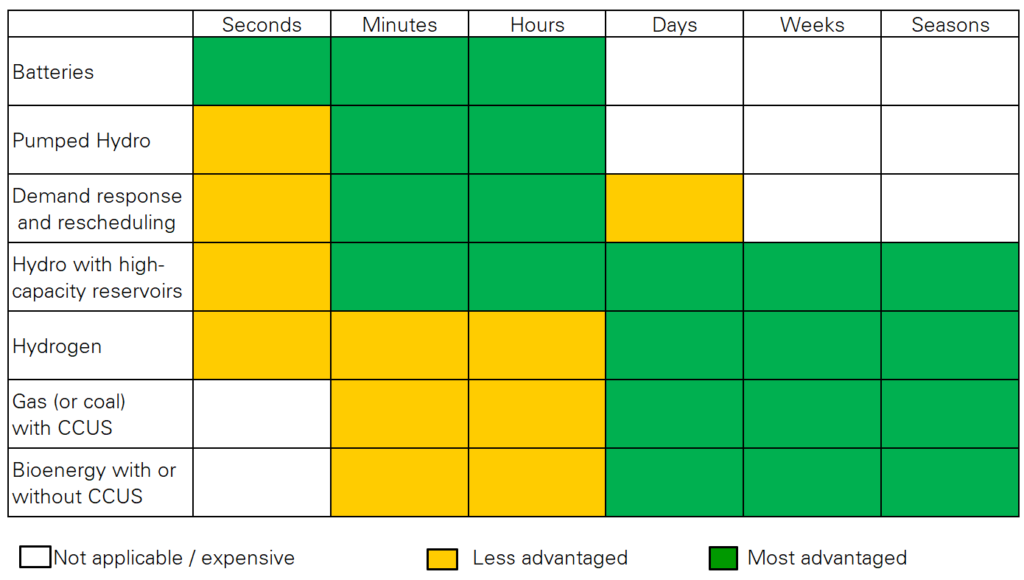

The move away from coal even for the incremental needs holds very significant implications. Carbon intensive fuel resources (coal, oil, natural gas) on which energy systems have hitherto depended on are abundant and storable. However, per the prevailing paradigm the energy produced however must be largely consumed instantaneously. Switching over to low carbon and intermittent sources will flip this paradigm – energy produced must substantially be stored for future consumption. This flip has very significant implications from resource harnessing, system design, engineering, and operations standpoints. Electricity require “flexibilisation” of the systems by modifying technical characteristics of assets, and also by adding energy storage facilities on a very large scale. At present, among the storage technologies batteries seem to be the favourite.

However, as the graphic comparing various technologies indicates, a range of diverse solutions are needed to address various kinds of storage needs. Development of solutions that serve for extended periods have come to be a challenge. For example, large storage hydro projects that serve longer term needs have become exceedingly difficult to build. At the same time, these will be important from a grid balancing and stability perspective. Carbon Capture (Utilisation) and Storage CCS/CCUS are the other technologies that could allow for conventional fossil fuels to operate without the attendant environmental damages. The new energy paradigm has and will completely transform the way various conventional and renewable technologies interact with each other, and their efficient nexus will be indispensable for ensuring a just energy transition.

The dynamic characteristic of the future electricity systems will demand huge competence and preparedness on part of the utilities, and particularly the load serving entities that must manage the gyrations of both demand and supply ends of the system. Electricity delivery systems would have to rapidly modernised, ‘hardened’ to withstand weather or related events (including fires) and made more resilient than before, to enable prompt restoration. The changing geopolitical dynamics will only increase supply uncertainties and utilities have to be more prepared than ever before to deal with such black swan events. The blackouts in Texas and more recently in China are testament to the need of a resilient, efficient and self-supporting electricity systems. Utility modernisation thus must be an integral part of climate event response. This will involve costs, efforts and new competencies that must be acquired.

It will also require large capital outlays, and in all likelihood will have large tariff and/or fiscal implications, and therein lies the Achilles heel of the Indian energy story. For all the progress made in modernising India’s energy sector, electricity distribution reforms remain a significantly unfinished agenda. Over the past two decades and especially consequent to the Electricity Act, 2003 the electricity sector has witnessed focused attention on restructuring, Corporatisation, independent regulation and markets. However, the distribution segment has not turned around, despite some ebbing of the financial losses at times in response to initiatives like Ujwal DISCOM Assurance Yojana (UDAY), which transferred significant burdens to the State treasury. Aggregate Technical & Commercial (AT&C) losses, measured as the difference between energy supplied and energy collected for, are still at unacceptably high levels. Tariff distortions remain endemic with little or no unwinding of the deep-seated distortions. Open access, bulwark of the Electricity Act, 2003, has been resisted and often thwarted.

For all the good that it has brought about, Electricity Act 2003 did not structurally separate distribution and supply. Perhaps that was expedient at that juncture to get the rest of the substantial reforms out of the door. Since then, then proverbial tail has wagged the dog. Government of India, after being unable to bring about “carriage and content separation” is now looking at delicensing distribution and supply, much like generation had been delicensed in 2003. The effort has been questioned on political grounds and concerns have been raised regarding its implementability. A new draft of the National Electricity Policy (an earlier draft issued in February 2021 was commonly observed to be incoherent and unfocused) is also on the cards.

The energy sector and in particular the electricity segment as a fulcrum, must totally transform if we have to meet the planet’s climate and development goals. That will be the central focus of forthcoming discussions.